Interview | Julius Lukeš: The enfant terrible of Czech science

08. 10. 2024

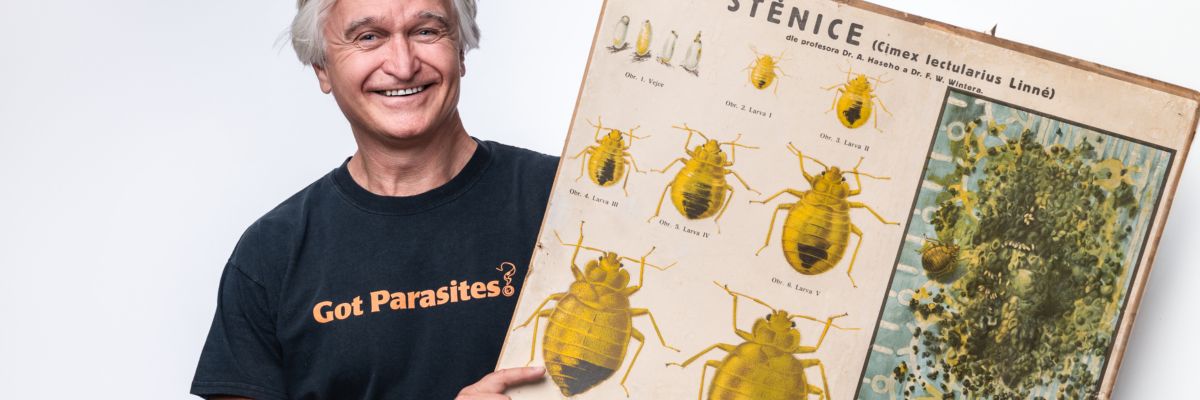

Years ago, he inadvertently made a name for himself by swallowing tapeworm eggs, nurturing the parasite inside his body for years. Julius Lukeš lives and breathes parasitology and is considered one of the world’s leading experts in the field. He is not one to stick to conventions, though, nor is he afraid to stir the pot. Read our interview with the parasitologist, first published in the 2/2024 Czech issue of A / Magazine, below.

*

Most people feel a bit nauseous at the thought of tapeworms, roundworms, or pinworms. What disgusts you?

Fools, communists, and other demagogues. But in nature, I haven’t yet come across anything that would make me shudder with disgust. I think parasites are beautiful organisms. Surprisingly, they evoke a lot of revulsion and, more importantly, fear in people, even though the vast majority have zero personal experience with them. At least once a week, someone emails me in a panic, convinced they have a parasite, even attaching a photo of their stool for me to examine.

Sounds like you have quite the inbox…

To me, it’s no different than if it were full of smiley faces. (smiling) I enlarge the image, study it, and form an opinion. But it’s almost never a parasite. In fact, over the past fifty years, we’ve practically eradicated parasites from our intestines. And by doing so, we’ve actually done ourselves a disservice.

What do you mean? Were people better off with worms in their guts?

Not if their intestines were full of them, of course. A hundred years ago, parasites caused our ancestors a lot of trouble. They suffered from severe infections, and on top of that, they were exhausted from hard work in the fields or forests. In the winter, they lacked vitamins because they often only had potatoes, cabbage, and maybe the occasional apple to eat. But today’s Europeans live very differently. In poor African countries, intestinal parasites are still a serious problem, but in Europe, most people have an abundance of food. So we can easily share that abundance with a worm or two.

But what good could such a tenant do us?

Believe me, it would give us much more than it would take. Various intestinal helminths and protozoa are our old friends. They’ve lived with us for millions of years, stimulating our immune systems. So they’re not true parasites, but rather what we call commensals: they take something from us, but also benefit us in return. However, until recently, medicine viewed these organisms as something that didn’t belong in the body and fought hard to eliminate them. That mission was successful, but over time, it’s becoming clear that their eradication has likely caused more harm than good.

Will we be missing our old friends after all?

In many ways, yes. Modern science has linked the eradication of intestinal parasites with the rise of allergies, autoimmune diseases, and even certain disorders, like autism. Some diseases that were once rare are now common. For instance, while a general practitioner might have diagnosed one case of Crohn’s disease per year thirty years ago, now it happens much more frequently. It seems that these changes are linked to the simplification of our microbiome. The “zoo” in our intestines influences far more than we used to think it does.

So, it would benefit our children to occasionally have worms again?

I believe so, yes. There’s no reason to panic if helminths show up in a kindergarten, for example. Quite the opposite. Even pinworms can have a very positive impact on kids’ immune systems.

“Many organisms, once considered parasites, are actually what we call commensals. They take something from us, but also benefit us in return.“ – Julius Lukeš

And what about lice?

External parasites, or ectoparasites, don’t bring us any benefits, so it makes sense to get rid of them. But that’s not the case with pinworms. I wouldn’t treat them at all. In today’s context, efforts to eliminate them are completely counterproductive. It’s similar to the annual outraged reports from parents about their kids getting diarrhea at summer camp. These dramatic news stories always amuse me.

But those affected kids are usually not happy campers...

Maybe not in that moment, but in the long run, both the kids and their parents should be grateful for the experience. For our super-obese population, an occasional bout of diarrhea is actually beneficial. Plus, being in nature gives kids the chance to expand their intestinal zoo a bit. It is during childhood that the microbiome is formed, so kids should spend as much time as possible outside, with animals, playing in mud… Teaching them to wash their hands before and after eating is, in my opinion, nonsense. During the pandemic, it made sense, of course. But otherwise, excessive hygiene is more harmful than helpful.

|

Prof. RNDr. JULIUS LUKEŠ, CSc.

Julius Lukeš studied parasitology at the Faculty of Science at Charles University in Prague. Since 1987, he has worked at the Institute of Parasitology at the Biology Center of the CAS, which he led from 2012 to 2022. Lukeš has also worked at universities in Amsterdam and Los Angeles and the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research in Toronto. His research focuses primarily on the molecular biology of parasitic protozoa and marine protozoa from the diplonemid group. He has published over 400 research articles and lectures at the University of South Bohemia. In recent years, Lukeš has been elected to several scientific organizations, including the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS), EMBO, and in May 2024, the U.S. National Academy of Sciences, where he is currently the Czech Republic’s sole representative. |

Can adults also work on improving their microbiome?

Certainly. For example, by eating a varied diet. People who live on canned food or eat just bread and butter every day simplify the microscopic world in their bodies. On the other hand, those who travel a lot and try local foods or frequently visit ethnic restaurants have a richer internal zoo, which positively impacts their health.

It seems that the diversity of one’s microbiome partly depends on the size of one's bank account.

You’re right. A Danish study confirmed this connection. Wealthier people do indeed have a more diverse gut zoo. How- ever, even a rich person can have a disrupted microbiome. And “fixing” it isn’t as simple as snapping your fingers. It’s a long process. Unless, of course, the person gets the chance to undergo a fecal transplant.

A what?

It’s a procedure where a patient receives stool with a healthy microbiome via an enema. It’s mainly used to treat intestinal Clostridium infections, ulcerative colitis, or Crohn’s disease. However, it’s still a relatively rare procedure, primarily because it’s logistically challenging. And donating stool isn’t as uplifting an activity as donating blood, after all. But fecal transplants have been proven to save lives, so expanding stool donor databases is definitely something that should be done.

Does this mean there are fecal banks as well as blood banks?

Yes. The first one in the Czech Republic was established last year at Thomayer Hospital in Prague. They store hundreds of stool samples that can be administered to suitable patients when needed. By the way, in the USA, stool has even been granted the status of a drug that can only be administered by a doctor. This is because fecal transplants were being performed widely on the black market.

Can you explain why?

In recent years, the Clostridium difficile bacteria, which causes severe diarrhea, has spread significantly throughout the USA, killing tens of thousands of people every year. Fecal transplants are the best treatment for this condition, but for a long time, it was taboo among doctors. That’s why the affected people started trying to procure the treatment themselves. It wasn’t very safe, which is why legislation was changed to deter DIY procedures. Nowadays, if you were to just donate your stool for a transplant in the USA, you’d be committing a crime.

Let’s go back to the situation at home… Isn’t there a more elegant way to help patients with a damaged microbiome? Without involving excrement?

We don’t know how just yet. But I believe that in the future, it will be as simple as swallowing a pill containing worm eggs, which will take care of everything in the intestines. Clinical trials in this direction are already underway in other parts of the world. The most important thing will be ensuring that the parasites can’t reproduce inside the human body. Such pills could then be prescribed by doctors for certain intestinal diseases as well as various allergies.

“Modern science has linked the eradication of intestinal parasites with the rise of allergies, autoimmune diseases, and even certain disorders.” – Julius Lukeš

Not all parasites have the potential to become heroes, though…

You’re right. There are countless villains among them. For instance, protozoa of the genus Plasmodium, which cause malaria, are responsible for half a million to one million human deaths annually. They are the biggest parasitic killers on Earth. Trypanosomes are also archetypal villains. If you get Trypanosoma brucei or Trypanosoma cruzi, you either die or suffer severe lifelong consequences. Trying to find any good in these organisms would be a bit perverse. In their case, the goal of parasitology is clear: to prevent them from harming people.

And are we succeeding?

Scientists have been trying to develop an effective malaria vaccine for fifty years. Only now have vaccines developed by British researchers shown promising results. In contrast, the fight against sleeping sickness has taken a turn for the better thanks to a new Franco-Swiss drug. While hundreds of thousands used to die each year after being bitten by an infected tsetse fly, today it’s only around a thousand people. That is a huge success.

I heard you have personal experience with the tsetse fly.

Yes. A colleague once needed to take detailed photos of it, so I let the fly “pose” on me. It bit me, and all I could do was hope it wasn’t infected. In hindsight? Not my brightest idea.

No wonder! Hosting such creatures in one’s body is not exactly common.

But it could be. The tapeworms lived inside me for quite a few years, and I practically didn’t even notice them. I had no health issues. In fact, I’m convinced that it actually benefited my body, just like my other experiments with parasites.

So your tapeworms are no longer alive?

Unfortunately, no. A few years ago, during a Canadian expedition in the Caribbean, I was goaded into tasting the fruit of the manchineel tree, which is the most poisonous tree in the world. I didn’t know that at the time. It wasn’t until later that I learned that one in four people dies within 24 hours of eating this fruit. The tapeworms didn’t survive, but luckily, I did.

It didn’t affect you at all?

I felt pretty awful – I was vomiting and hallucinating, and there was a strong metallic taste in my mouth. But by the evening, my colleagues and I were already chuckling over the whole experience.

What does your wife think about these experiments?

She would just say, “no comment!” (laughter) She doesn’t even try to talk me out of my ideas anymore. Thankfully, she doesn’t have any exaggerated fears of catching something from me. But I think she does worry about me from time to time…

Aren’t you ever afraid for your own wellbeing?

Not when working with parasites. But I do get scared, for example, when I’m traveling in the tropics with a driver who’s falling asleep at the wheel or going too fast. People instinctively fear parasites and consider them dangerous, but then they jump into a car, weave through traffic, and overtake on hills without a second thought. In those cases, mere seconds determine whether something terrible will happen or not, yet people accept that risk. My experiments are much safer compared to the behavior of many drivers.

You must have quite a strong constitution.

It’s true that I hardly ever get sick. Even with multiple exposures to COVID-19, I managed to avoid it. I’d say my strong immunity is related to the fact that, thanks to frequent travels and my experiments, I have quite a diverse zoo living inside my body. I also do 111 push-ups every morning when I wake up and I run a lot, though it’s not as easy anymore, now that I’m over sixty. (laughter) On top of that, I’ve been practicing cold exposure for years. I started in 2014 – so before it became trendy – as part of my preparation for the Tara Oceans expedition to the Arctic, which mapped microscopic life in our oceans. Since then, I’ve made it a habit to stop by the river and swim against the current every morning on my way to work, basically no matter the weather.

You’re known for wearing only T-shirts and shorts and often go barefoot, almost year-round. Do you always feel that warm?

Too many clothes have always bothered me, and this way, life is just simpler. Plus, when I wear pants, I tend to overheat. But I do recognize that there are limits, so I will wear long pants and shoes to classical music concerts or the opera. However, it’s rare to see me in a suit. And I won’t give up my animal-themed T-shirts, either!

I heard you choose them based on your mood.

That’s right. In the morning, I peek into my closet and my mood decides for me. Apparently, my students held this belief that if I showed up on exam day wearing a shark on my chest, I tended to be tougher. But if I had a dolphin on my shirt, the exams were supposedly more relaxed. I’m not so sure about that, though.

Has your unconventional way of dressing ever gotten you into trouble?

A few times, yes. For instance, I was once escorted out of an honorary doctorate degree ceremony at the University of South Bohemia because of the dress code. The rector at the time asked me to apologize, but my dean told him the chances of that happening were about the same as being hit by a meteorite. (laughter)

Haven’t you ever donned formal wear? Not even for your own wedding?

For my wedding, I did. I got married in 1989, and I’ve only been wearing shorts consistently for about the past twenty years. Before that, I would occasionally wear a pre-WW2 tailored suit inherited from a wealthy uncle. The last time I squeezed into a suit was in 2016 when I was invited to the Czech Lion Awards ceremony. My plan had been to run to the restroom right before going on stage and quickly change into shorts, but my wife vetoed it. It could’ve been pretty funny, though.

One could say you’re somewhat of a provocateur.

I guess, but to me, it’s not about seeking attention. It’s more of a resistance to authority, something my father instilled in me. I grew up in Czechoslovakia during the height of socialism, and the authorities of that time were tragically laughable. I felt the need to push back against them, and that’s likely stuck with me since. My dad also advised me to always take a different path than the majority, and I’ve taken that to heart.

So you swim against the current not just at dawn in the Vltava River… No wonder some of your colleagues call you the enfant terrible of Czech science. Does that label fit you?

Maybe in the past, but I’m much calmer nowadays. The years have sort of “mellowed” me. (laughter) Even on expeditions, I don’t do as many crazy things and don’t take as many risks as I used to. I’ve traveled to 111 countries, and my experiences have taught me to recognize warning signs and avoid unnecessary dangers. But I have enough wild stories from my travels.

Tell us…

In Gambia, for instance, they threatened to slit our throats open, and in Papua New Guinea, we narrowly avoided an ambush thanks to pure instinct... I also vividly remember a time in 2009 when, after a month-long expedition in Ecuador, I was supposed to fly to Canada. I didn’t realize until I was at the airport that I had taken my other passport by mistake, the one without the visa. The situation looked dire, but I actually managed to smuggle myself onto the plane and eventually made it to Canada.

How? Did you sneak under the turnstiles like in the movies?

Exactly. They didn’t discover it until we landed in Atlanta, and it caused quite a commotion, but the Academy had my back at the time. In fact, the Academy has helped me out of tight spots more than once during my career. I’m not one to dish out praise lightly, but I think it’s one classy organization. It’s apolitical, stable, and respected worldwide. And I’m not just saying that to curry favor with the popular science magazine the institution publishes. (laughter) I’m simply glad I work for the Academy, and I wouldn’t change a thing.

Did you always know this was what you wanted to do? Were you drawn to science from a young age?

According to my mom, yes. In our family, the butcher’s trade had been passed down for two hundred years, but since I always loved animals, it was clear I wasn’t going to be slaughtering cows anytime soon. Nature fascinated me even as a little boy – I studied bugs, conducted experiments... When I was about seven, my mom and I were walking past the university in Olomouc, and apparently, I announced I wanted to study there. But I ended up on the other side of the Czech Republic, studying natural sciences in Prague.

Why did you choose parasitology?

Shortly after starting at university, the word on the street, specifically Viničná Street, in the student pub called Uterus, was that the Department of Parasitology had a liberal environment and good professors who didn’t spew communist hogwash. Plus, its study program offered the chance to travel to tropical socialist countries, which intrigued me. Once I got the chance to check out the department, I found out this was all true, so I stayed. My classmates and I were incredibly passionate about our studies and pushed each other constantly. That’s how I realized just how fascinating parasites are.

“A clever parasite won’t kill its host, because it would die along with it. It drains the host in moderation to avoid cutting off its own source of sustenance.“ – Julius Lukeš

How many species of parasites are there in the world?

Millions. Every free-living multicellular animal species has more than one parasite. In fact, parasitism is the most common “lifestyle” on this planet. Tapping into someone else’s energy and letting them take care of everything is simply more advantageous than having to secure all of life’s necessities on your own. This strategy is so attractive that many originally free-living organisms have gradually resorted to parasitism.

How is it that a primitive parasite can outsmart a much more complex organism and feed off it so easily?

There’s no simple answer to that. Each parasite has found its own way. Parasites don’t have one single, unified tactic. Their only common denominator is that they live at someone else’s expense. To do so, they’ve developed various methods over millions of years – many of which are so ingenious that scientists have been trying to copycat them for years.

What are some examples?

Take a tick, for instance. When a tick latches onto us, it needs to go unnoticed, so it injects substances that reduce pain and inflammation. A leech, however, doesn’t want the blood it is sucking from its host to clot in its mouth, so it produces anticoagulants. All these substances can then be extracted and used for medical purposes.

|

A TRUE BUG MIRACLE In 2023, Julius Lukeš’s team succeeded in isolating a previously unknown type of parasite related to trypanosomes from a true bug found in the Český ráj region, which managed to develop a unique mechanism for encoding its genetic code. The researchers decoded the genome of this protozoan and described how this deviation occurred. The discovery, which made it to the cover of Nature, could potentially aid in the treatment of certain human genetic disorders, such as cystic fibrosis. “We could ‘repair’ a whole range of currently incurable conditions using the mechanism this protozoan has devised,” Lukeš explains. |

Medicine has a lot to learn from parasites, I see…

Absolutely. Studying the biology of parasites can be of great benefit to medicine. Recently, we discovered a previously unknown parasite related to trypanosomes that has altered its genetic code in a unique way. We described how this deviation occurred, which could potentially be used to treat certain currently untreatable genetic diseases in humans. Thanks to a trypanosome from a common bug we caught in the Český ráj region, medical textbooks may need to be rewritten.

You have a particular fondness for trypanosomes, don’t you?

They’re my “darlings.” I’ve studied them for most of my life, and they’ve been a constant throughout my career. About every five to ten years, I switch research topics and dive into something new, but I always find my way back to trypanosomes.

In other words, you take a little scientific “detour” every few years?

You could say that. In science, it’s called a “lateral shift,” and not many researchers take these detours since they’re quite risky. In a new field, no one knows you, you have to convince your colleagues that it’s not just some superficial whim, and above all, you need to secure funding despite basically being a newcomer. There’s always a chance you could hit a dead end. But I have this restlessness inside me, which compels me to take the risk now and then.

What are you working on now?

Lately, I’ve been fascinated by alternative genetic codes. But I always try to work on several things at once because I make better progress with some of them than with others. Besides the genetic codes, I’ve also been studying marine organisms called diplonemids, endosymbionts, which are bacteria living inside protozoa, and, of course, my darling trypanosomes. My colleagues probably see me as a bit of a shaker-upper, but it helps our, I’d say, decent productivity.

Do you plan to expand your scientific repertoire even further?

I’m tempted to, but I’m not sure if I’ll manage another research “shift” before I retire. However, I want to continue my research at full throttle, as long as my health and mind allow it. And as long as they save me a desk somewhere in the corner at the institute. (laughter)

Do you ever find time to relax?

Of course! I enjoy nature, I run, I spend time with family and friends... I also love classical music. I played the piano for many years, but my imperfect playing resulted in me becoming a mere listener. I attend concerts, and my wife and I sometimes host musical performances at our house in České Budějovice for dozens of people. I also try to read something unrelated to science at least an hour every day to avoid becoming too blinkered. I particularly enjoy travel books, especially older ones.

In your emails, you always sign off with, “nazdááárek Jula” [editor’s note: byeeeee, Jula]. Do you actually have any attachment at all to the degrees that precede and come after your name?

None at all. Academic titles might play a role in the educational hierarchy, but in science, they’re of little import. What matters is what a person has achieved in their field. When someone brandishes their professorships and doctorates, I lose interest. It’s a waste of time during introductions. I just feel most comfortable as Jula. (smiling)

Written and prepared by: Radka Římanová, External Relations Division, CAO of the CAS

Translated by: Tereza Novická, External Relations Division, CAO of the CAS

Photo: Jana Plavec, External Relations Division, CAO of the CAS

The text and photos are released for use under the Creative Commons licence.

The text and photos are released for use under the Creative Commons licence.

Read also

- Moss as a predator? Photogenic Science reveals the beauty and humor in research

- How does the Academy Council plan to strengthen the Academy’s role? Part 2

- How does the Academy Council plan to strengthen the Academy’s role? Part 1

- Ombudsperson Dana Plavcová: We all play a role in creating a safe workplace

- ERC Consolidator Grant heads to the CAS for “wildlife on the move” project

- A little-known chapter of history: Czechoslovaks who fought in the Wehrmacht

- Twenty years of EURAXESS: Supporting researchers in motion

- Researching scent: Cleopatra’s legacy, Egyptian rituals, and ancient heritage

- The secret of termites: Long-lived social insects that live in advanced colonies

- Two ERC Synergy Grants awarded to the Czech Academy of Sciences

The Czech Academy of Sciences (the CAS)

The mission of the CAS

The primary mission of the CAS is to conduct research in a broad spectrum of natural, technical and social sciences as well as humanities. This research aims to advance progress of scientific knowledge at the international level, considering, however, the specific needs of the Czech society and the national culture.

President of the CAS

Prof. Eva Zažímalová has started her second term of office in May 2021. She is a respected scientist, and a Professor of Plant Anatomy and Physiology.

She is also a part of GCSA of the EU.