Pop culture reflects contemporary values and behavioral patterns, says historian

11. 02. 2025

As a teen, Veronika Pehe dreamed of becoming a filmmaker. Now, though, the researcher from the Institute of Contemporary History of the CAS doesn’t direct films nor TV shows – she studies them. According to Pehe, they function in many ways as testimonies of their time. What can Czech post-Velvet Revolution productions reveal about how our society changed after 1989? Find out below in our interview with the researcher, which first came out (in Czech) in the quarterly A / Magazine of the CAS.

Ill-fitting purple blazers, the notorious mullet hairstyle, garish nylon tracksuits… What comes to mind when you hear the word “the nineties”?

It’s true that this era had a very specific visual style, which is both attractive and repulsive in its own way. However, what primarily comes to my mind in connection with the 1990s is a kind of chaos. There were so many things happening all at once during this time period.

How did you experience the nineties?

I was born a year before the fall of the Communist regime, so I spent the early years of this decade in kindergarten in Munich, where we lived at the time. I started elementary school in Prague. I rode my bike, watched VHS tapes of Disney movies, and like many of my peers, I had a Tamagotchi.

Veronika Pehe from the Institute of Contemporary History of the CAS.

Did you also succumb to the charm of the virtual pet?

Just for a bit. I was more interested in public affairs. Every evening, I would watch the news on TV with my parents. For instance, I vividly recall the debates in 1998 about the opposition agreement between [Czech political parties] ČSSD and ODS. Watching the news seemed more entertaining to me than, say, sitting through Esmeralda, the telenovela I’d occasionally watch at my grandparents’ house.

Your interest in politics seems to run in the family. Your father, political analyst Jiří Pehe, was working as an advisor to Czech President Václav Havel at the time. I assume politics was often discussed at home.

It definitely was, and I was glad for it, having enjoyed it from a young age. I thought it important to stay in the loop and have my own opinion on public matters. For instance, when the TV crisis at Czech Television erupted in late 2000, early 2001, I was thirteen. I attended the protests with my parents – not because they told me to, but because I came to the conclusion myself that I should go.

Let’s go back to the “nineties,” which you study intensively. Why did you choose this era in particular?

It’s a liminal, or transitional, period – when the old has ended, but the new has not yet fully taken root. To me, that is what makes this decade so compelling to study. As a cultural historian, I’m particularly interested in society and its culture, which underwent significant changes at the time. In my view, the “nineties” played a key role in shaping how people in the Czech Republic and other former Eastern Bloc countries relate to the world today. Many crucial aspects, like our relationship to property, were defined during this time. It was simply a period of significant change that also influenced people’s everyday behavioral patterns and values.

How, exactly?

For example, with the boom in entrepreneurship, politicians, media, and economic experts began to emphasize the need for society to adopt a market-oriented mindset. The idea that people had to change their way of thinking [in the Czech Republic] became a prominent leitmotif of the early nineties. The new era also placed a strong emphasis on personal responsibility and merit. The phrase “every person is the architect of their own fortune” became popular, and people’s notions of success – and who deserves it – underwent a major reconfiguration.

You study these changes through the media of films, TV series, and novels from that time. Can fiction serve as a historical source?

I believe popular culture is a suitable and fascinating medium through which to observe cultural trends in our society. It reflects contemporary values and behavioral patterns. Films are works of fiction, sure, but to some extent, they can be viewed as documents of their time. Of course, they don’t map history in detail, but they can capture shared perceptions of the era.

Veronika Pehe discovered the allure of filmmaking when in high school.

What does Czech film production from the nineties reveal about the zeitgeist of the time?

It shows, for instance, how naive people were about what the free market could bring them. A popular genre of the time was the so-called privatization [or restitution] comedy, in which the protagonist usually becomes unexpectedly wealthy or suddenly comes into property – a storyline based on actual real-life experience of the era. The humor in these films often stemmed from the fact that the characters didn’t know how to handle their newfound wealth. They might have come into financial capital, but they lacked cultural capital.

Like the protagonist in the movie The Inheritance or Fuckoffguysgoodday (Dědictví aneb kurvahošigutntag)?

Exactly. This successful 1992 film by Věra Chytilová says a lot about the mood of the nineties. Other films of the genre depict entrepreneurs trying to start a business while lacking the aptitude for it, only for it to usually end in failure. Unlike the protagonists of Polish films from the same period.

Polish film entrepreneurs were more successful?

In Polish cinema of that time, we more often see this type of capitalist revolutionary fervor in films featuring successful self-made individuals. A worker might work their way up to become a major industrialist. Interestingly, these films often had female protagonists, which can’t be said of Czech films from that period. Czech notions of transformation were clearly very masculine.

How did this manifest in Czech cinema?

It is almost always a man starring in the movies, with women appearing more as objects of the main character’s desire. Every businessman has a provocatively dressed secretary, and every doctor has a nurse in an absurdly short uniform. The promise of social mobility and wealth, a common motif in nineties’ films, was primarily directed at men in our popular culture. Women could improve their economic situation only by using their bodies – through prostitution, seduction of wealthy men, and so on.

For that matter, nudity was abundant in films of the time.

And not just in films. It appeared frequently in advertisements, and it was common for every newsstand to display pornographic magazines. Out of films, it would be remiss not to mention the two Playgirls films by Vít Olmer, which capture the environment of a brothel quite explicitly. Prostitution was also a theme in Nudity for Sale (Nahota na prodej) by the same director, one of the few Czech attempts at making a Hollywood-style action movie during that period. Unfortunately, it wasn’t very successful.

One of the few? Were Czech filmmakers not interested in emulating Hollywood?

They were, but this type of films is very expensive, and most couldn’t afford them. Incidentally, one of the most popular genres in Poland during the nineties was gangster films. Thanks to greater continuity in the funding of Polish film studios, Poland was able to produce more expensive films than we could. While the Czech Republic didn’t produce blockbusters, it made a relatively large number of films compared to neighboring Slovakia, whose film industry was decimated by the privatization of the Koliba studios in Bratislava. Until the situation stabilized, only a handful of films were made there each year.

Back to the Czech Republic. Which film from the nineties do you think best captures the spirit of its time?

That’s hard to say. Privatization comedies may reflect the expectations of the era, but they don’t really capture its reality – they’re highly exaggerated. I believe Milan Růžička’s 1992 film She Picked Violets with Dynamite (Trhala fialky dynamitem) contains many motifs characteristic of the period. It’s zany, illogical, but includes themes like failed entrepreneurship, problematic gender dynamics, clashes with the West, and even racism – a significant phenomenon of that time.

Could you remind us what the comedy is about?

It’s about a family that starts a travel agency, planning to take tourists from France to the Czech Republic. The film follows one of their trips from Paris, which ends up a fiasco. On the one hand, the movie touches on a sense of inadequacy felt by the Czech protagonists compared to their Western counterparts, but at the same time, it’s full of patriotism. The protagonists may be aspiring to catch up with the West, but they also think they know everything best and look down on foreign cultural practices.

They’re evidently afflicted by our notorious Czech small-mindedness [čecháčkovství]…

Exactly. They don’t feel the need to imitate anything because they’d rather do everything their own way, and they’re happy with that. This attitude, I think, perfectly reflects the mindset of the time. While She Picked Violets with Dynamite isn’t exactly a cinematic gem – in fact, it’s an objectively awful movie that few can endure – it still says a lot about the Czech 1990s.

Have you really finished all the films of that era to the end?

Yes. A large portion of so-called transitional films admittedly doesn’t hold much artistic merit, so watching them from start to finish can be quite grueling. But what wouldn’t one do for research, right? (smiling) I probably suffered the most watching the zany comedy The Canary Connection (Kanárská spojka) from 1993, which was shot on the Canary Islands and starred nearly every Czech celebrity of the time. The production was funded by a private company, so the entire film was essentially one big product placement. But in a way, this too illustrates how the film industry – and society at large – functioned back then.

You’ve also studied how post-1989 Czech cinema portrayed the pre-Velvet Revolution era. What conclusions did you draw?

I focused primarily on how various pop culture productions related to the communist period and how filmmakers used various imagery to process that past. I observed that a trend in the 1990s was to approach our postwar history through comedies and stories of ordinary people who didn’t agree with the regime but expressed their dissent only through small gestures.

For example?

Take Jan Hřebejk’s film Cosy Dens (Pelíšky) from 1999, for instance, and the character of Kraus – a hero of the anti-Fascist resistance, played by Jiří Kodet. He’s a staunch anti-communist, but he only shows it at home. In one scene, though, he gets so riled up that he storms out onto the balcony and shouts, “Workers of the world, kiss my…!”

According to Veronika Pehe, pop culture is a suitable medium through which we can observe various societal trends.

For those who haven’t seen it, I think it’s not hard to fill in the rest.

After delivering that line, Kraus goes back inside and tells his wife, “That sure felt good!” Similar insignificant gestures bring the protagonists of these films a sense of relief and personal moral satisfaction. I call it “petty heroism,” and it appears even in later films like Identity Card (Občanský průkaz), directed by Ondřej Trojan in 2010 based on Petr Šabach’s short stories. In the film, the teen characters rip the pages of their ID cards. It’s essentially trivial…

…but to them, it feels like an act of bravery.

To them, it’s a symbol of their dissent against the regime. However, after the turn of the millennium, Czech cinema gradually shifted to films depicting protagonists who directly opposed communist power. Naturally, these stories – just as they did historically – end badly for the heroes. This wave of dramatic heroic movies continues to this day. Case in point, last year’s Brothers (Bratři) film, which is about the Mašín brothers’ escape from Czechoslovakia, retells recent history as an action thriller.

So Czech filmmakers have transitioned from family comedies to action movies?

You could say that. The film aesthetics have also changed. Cinematography in the 1990s depicted socialism quite vividly – even Cosy Dens that I mentioned earlier are visually styled using a warm, pleasant palette. But with the shift in genre and focus to great heroic narratives, filmmakers began using colder hues.

And so onscreen socialism gradually turned gray.

Yes. That’s precisely how the dynamics of cultural memory work – the closer a person is in time to a period being remembered, the more ambivalent their relationship to it. With more distance, the past appears in a more clearly defined outline. That’s why films about the communist regime gradually shifted from colorful portrayals to shades of gray. Interestingly, historical research operates on the opposite principle.

What do you mean?

The more in-depth we study a particular period, the more ambiguities and complexities we uncover. No era can be easily categorized. The same applies to the communist period in our country. Of course, no one is disputing the regime’s criminal nature, but the image of society at that time was far more complicated.

The film Cosy Dens (Pelíšky) follows the life stories of three generations of men and women in Czechoslovakia at the end of the 1960s.

Do you think films and series influence and shape collective memory about this chapter of our history?

Until recently, movies like Cosy Dens or the show Wonderful Times (Vyprávěj) were a fairly significant source of knowledge about socialism for younger generations. But that’s already changing. When I lecture students about my work today, I find that these media are now passé for them. Their world occurs in the digital sphere, and cultural consumption patterns have shifted. Generally, young people just haven’t seen that many films about the communist era, if any at all.

Unlike you… Just how many times have you seen Cosy Dens?

I’d say a hundred or so. But many other works I revisit more purposefully instead of watching them repeatedly in full. When I watch them for the first time, I take notes and write down quotes, and then I only replay key moments. That is, if I’m lucky enough to have the film available on DVD or on my computer. Otherwise, I have to go to a film archive or the Czech Television archive to view it there.

No popcorn, soda, and cozy evenings on the couch, then?

Unfortunately, that’s not how my research looks like. Although I study films, I also examine their social, financial, and production contexts. I look for interviews with filmmakers, reviews, and discussions sparked by the work in question. However, in my current project, I’ve shifted from studying films to focusing on educational programs and magazine production of the 1990s.

Does that mean you’re flipping through old issues of Bravo [European teen magazine]?

Not exactly, but Bravo is undoubtedly an interesting source for understanding the aspirations of the younger generation back then. My focus now is mainly on how people’s attitudes toward work evolved during the transitional period. I’m interested in what it meant to them that they could start businesses, what was their vision, and how they actually went about it. So I’m working through periodicals like Úspěch (Success), which captures the mindset of entrepreneurs at the time. The publications back then also frequently highlighted how much Czechs were lagging behind the West. The vision of someday catching up to it was an important motivator – even in magazines like Bravo, which was devoured by thousands of teenagers in its heyday.

What were you like at that age?

I enjoyed school because I’d always been a bookish type. Besides public affairs, I was also interested in our family history. I would often ask my parents or grandfather to tell me about their lives. Stories reflecting the key events of the 20th century fascinated me from an early age.

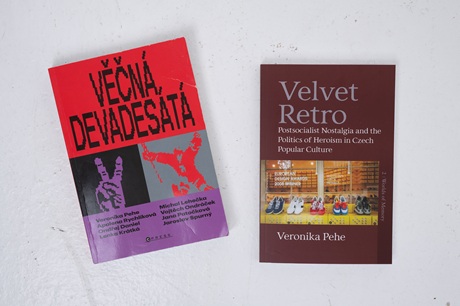

Veronika Pehe has explored Czech film and TV productions of the post-Velvet Revolution era in several publications.

So a career as a historian seemed a natural choice…

I didn’t think so at the time. As a kid I was also quite creative – I painted a lot, played various instruments... In high school, I discovered the magic of filmmaking. I would haul a camera with me everywhere and was always shooting something. Mostly documentaries. For example, about the election to our high school student council.

Did you dream of becoming a filmmaker?

For a while, yes. I even wanted to apply to the Film and TV School of the Academy of Performing Arts in Prague (FAMU), but then I realized I didn’t have the talent for it – I lack spatial imagination. In the end, I chose to go study comparative literature and film studies in London. I soon discovered, though, that I was more interested in the societal role of these images in the films than in their artistic aspects or in how well an actor performed a role or how a scene was lit.

Why did London win you over?

I attended an English high school in Prague, where we were heavily encouraged to go study in Britain. But I mainly wanted to go abroad because I felt a strong need to emancipate myself and become independent.

You returned with a PhD degree, so the bid for independence seems to have worked out.

The nine years I spent in London had a significant impact on shaping my worldview. Because my father was a publicly active figure, I came from a home with a certain cultural and social capital. But in London, that wasn’t much use to me – there I was just one of millions of Eastern European migrants. I had to integrate into the university environment and earn my living. It was an incredibly valuable experience for me.

Did you have any part-time jobs or join the gig economy?

Constantly! I worked in sales for cosmetics and clothes, waited tables, and worked in a café. British society is deeply class-based, in a way I wasn’t familiar with from the Czech Republic. I encountered stark social differences and witnessed a lot of injustice.

Is that why you eventually came back and settled in Prague?

It was more because London just felt too big for me. Commuting an hour and a half to work or university and then back in the evening, always in a rush, stressed out... I wanted a change, so I applied for postdoc positions across Europe. I ended up in Florence for a year. After that, I worked in Warsaw for a while in an editorial office, where I also met my husband. When we found out we were going to have a child, we decided Prague would be ideal for family life.

Research and motherhood – has it been a challenging balancing act?

My son is six now, so it’s more manageable. But I think the issue of parenthood hasn’t been structurally resolved in Czech academia yet. For example, each funding provider has different rules on whether and how they allow female researchers to combine maternity leave with research project work. These rules should be clearer so that women know it’s genuinely possible to have children and still be actively engaged in their scientific field and work.

You’re leading a research team of your own at the moment. What do you do when you’ve “clocked out” and need to clear your head?

Researchers usually do their work because they enjoy it. It’s quite common for us to remain somewhat mentally immersed in it all the time. But, of course, it doesn’t hurt to try to disconnect now and then. For me, a good way of doing that is going on a hike in nature or a family bike trip.

So you’re a sporty type?

Not at all. I don’t have the disposition for sports. I’m simply not good at it, and because of that, I don’t particularly enjoy it, either. Back when I was studying at uni, I liked to go rock climbing, but now I’m perfectly satisfied with occasional family hikes. However, I find the best way for me to unwind is reading fiction, especially historical novels.

A touch of professional deformation, perhaps?

Maybe a little, but I choose books I don’t have to think about from a professional perspective. I don’t engage in critical analysis – I just let myself get drawn into the story and enjoy it. Recently, I got hooked on Šikmý kostel (The Leaning Church), a several-volume novel chronicle by Karin Lednická. For me, texts are both work and leisure. A historian’s work involves reading, writing, and discussing texts. Everything revolves around the written word. And in my case, quite often around films, too.

|

M.A. VERONIKA PEHE, Ph.D.

Veronika Pehe studied comparative literature and film studies at King’s College London and University College London in the UK, earning her doctorate in cultural history from the latter institution. At the Institute of Contemporary History of the CAS, she co-leads the Department of Knowledge, Culture, Expertise. Her work focuses on the systemic transformation after 1989, Czech history in the 1990s, and the cultural history of Central Europe in the latter half of the 20th century. She is the author of the book Velvet Retro: Postsocialist Nostalgia and the Politics of Heroism in Czech Popular Culture and co-author of Věčná devadesátá: Proměny české společnosti po roce 1989 (The Eternal Nineties: Changes in Czech Society after 1989). In 2022, she was awarded the Lumina Quaeruntur. |

The interview first came out (in Czech) in the 3/2024 issue of the quarterly A / Magazine of the CAS:

3/2024 (version for browsing)

3/2024 (version for download)

Written by: Radka Římanová, External Relations Division, CAO of the CAS

Translated and prepared by: Tereza Novická, External Relations Division, CAO of the CAS

Photo: Jana Plavec, External Relations Division, CAO of the CAS

The text and photos are released for use under the Creative Commons license.

The text and photos are released for use under the Creative Commons license.

Read also

- Moss as a predator? Photogenic Science reveals the beauty and humor in research

- How does the Academy Council plan to strengthen the Academy’s role? Part 2

- How does the Academy Council plan to strengthen the Academy’s role? Part 1

- Ombudsperson Dana Plavcová: We all play a role in creating a safe workplace

- ERC Consolidator Grant heads to the CAS for “wildlife on the move” project

- A little-known chapter of history: Czechoslovaks who fought in the Wehrmacht

- Twenty years of EURAXESS: Supporting researchers in motion

- Researching scent: Cleopatra’s legacy, Egyptian rituals, and ancient heritage

- The secret of termites: Long-lived social insects that live in advanced colonies

- Two ERC Synergy Grants awarded to the Czech Academy of Sciences

The Czech Academy of Sciences (the CAS)

The mission of the CAS

The primary mission of the CAS is to conduct research in a broad spectrum of natural, technical and social sciences as well as humanities. This research aims to advance progress of scientific knowledge at the international level, considering, however, the specific needs of the Czech society and the national culture.

President of the CAS

Prof. Eva Zažímalová has started her second term of office in May 2021. She is a respected scientist, and a Professor of Plant Anatomy and Physiology.

She is also a part of GCSA of the EU.