The first human presence in Europe securely dated to 1.4 million years ago

06. 03. 2024

When did members of the genus Homo first appear on the European continent after leaving Africa? Until now, the caves in Atapuerca, Spain, and Vallonnet, France, were regarded as the first inhabited locations in Europe (1.2–1.1 million years ago). However, new findings date the first human presence to 200–300 thousand years earlier in present-day western Ukraine. Evidence of the earliest hominin settlement comes in the form of stone tools found at the archaeological site of Korolevo. The groundbreaking results of the discovery, worked on by an international team led by Roman Garba from the Nuclear Physics Institute of the CAS and the Institute of Archaeology of the CAS in Prague, were published on 6 March 2024 in Nature.

The precise dating of Korolevo’s earliest occupation was made possible by recent advances in mathematical modelling combined with applied nuclear physics. Such unique results could not otherwise have been achieved without implementing a multidisciplinary approach and the synergy of all the scientific disciplines involved. “To answer the questions posed by archaeology and anthropology, we need to utilise the methods of both nuclear physics and geophysics,” Roman Garba explains.

The precise dating of Korolevo’s earliest occupation by hominins was made possible by a recent advance in mathematical modelling combined with applied nuclear physics.

— Czech Academy of Sciences (@CzechAcademy) March 6, 2024

R. Garba @romangarba, lead author of the study, sums up the findings and dating method used to determine the… pic.twitter.com/FmD9mGjWNK

The Ukrainian trace

The archaeological site of Korolevo is located in Zakarpattia Oblast, Ukraine, near the borders with Romania and Hungary, only 150 kilometres from Košice, Slovakia. In the past, the area was part of the former Czechoslovakia. Ukrainian archaeologists have been investigating the site for several decades, and it is a very important archaeological site on a European scale.

“The layer of accumulated loess and palaeosols here reaches a depth of up to 14 metres and contains thousands of stone tools. Korolevo was an important source of raw material for their production,” says Ukrainian archaeologist and co-author of the study, Vitaly Usyk.

“Seven periods of human occupation are represented in the stratigraphic layers at the Korolevo site, and at least nine different Palaeolithic cultures have been recorded here: hominins lived here from the earliest times until about 30,000 years ago,” adds the Ukrainian researcher who, due to the war situation in his home country, is currently working at the Institute of Archaeology of the CAS in Brno.

The first hominins came to Europe from Africa via the Middle East. Sites with radiometrically securely dated evidence of the oldest human settlements in Europe include Atapuerca in Spain (1.2–1.1 million years ago) and Vallonnet in southern France (1.2–1.1 million years ago). Now, even older evidence of human presence is provided by the finds at the Korolevo site in Ukraine (1.4 million years ago).

Cosmic rays and nuclear physics in the service of archaeology

The researchers chemically processed the cobble-sized clast samples from the Korolevo site and then analysed them by accelerator mass spectrometry at the Helmholtz-Zentrum Dresden-Rossendorf. (In 2022, an AMS laboratory was also opened by the Institute of Nuclear Physics of the CAS in Řež, Czech Republic, which would have made it possible to conduct the measurements in the Czech Republic, but at the time of the analysis of the samples, the equipment was not yet available for use).

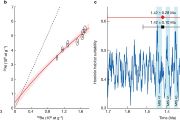

“At the Korolevo site, we specifically measured the concentrations of cosmogenic nuclides beryllium-10 and aluminium-26 which have different half-lives. These nuclides accumulate in the quartz grains when the rock is at the surface due to cosmogenic radiation from space, but they begin to decay when they become buried in the ground. The ratio of the two varies according to how long the clasts were buried beneath the ground surface. This allows us to calculate their age since burial,” Garba explains.

The scientists then used their own method based on mathematical modelling, known as P-PINI, to determine the age of the sediment layers. “This study is the first time our new dating approach has been applied in archaeology,” notes John Jansen from the Institute of Geophysics of the CAS.

Where the first humans came from

The new study changes the view of the dispersal routes of the first populations of the genus Homo. “Our earliest ancestor, Homo erectus, was the first of the hominins to leave Africa about two million years ago and head for the Middle East, East Asia, and Europe. The radiometric dating of the first human presence at the Korolevo site not only fills in a large spatial gap between the Dmanisi site in Georgia and Atapuerca in Spain, but also confirms the hypothesis that the first pulse of hominin dispersal into Europe came from the east or southeast,” Garba explains.

The lithic artefacts and a clast of quartzite from the oldest loess and palaeosol sediment layer of the Korolevo site in Transcarpathia, Ukraine.

The research was carried out on the basis of an agreement signed between the Nuclear Physics Institute of the CAS and the Institute of Archaeology of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine. The project was supported by the European Commission, the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports of the Czech Republic, the Czech Science Foundation, and the Charles University Grant Agency.

In addition to the Nuclear Physics Institute of the CAS, the Institute of Geophysics of the CAS, and the Institutes of Archaeology of the CAS in Brno and Prague, the Czech research institutions involved were the Department of Physical Geography and Geoecology of the Faculty of Science, Charles University and the Czech Geological Survey.

Foreign partners of the research are the Institute of Archaeology of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine (Kyiv, Ukraine), Helmholtz-Zentrum Dresden-Rossendorf (Germany), Aarhus University (Denmark), Department of Archaeology and History, La Trobe University (Melbourne, Australia), and Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv (Kyiv, Ukraine).

|

The prehistory of the modern human beyond the Nile River The first migrations of populations of the Homo genus from Africa occurred around two million years ago. Homo erectus, the ancestor of today’s modern human, crossed what is now the Arabian Peninsula towards Asia (eastward) and Europe (westward). Over time, H. erectus dispersed throughout Eurasia, where it diversified and evolved over the next hundreds of thousands of years. Later, around 500,000 years ago, Homo heidelbergensis, another human species, also originating in sub-Saharan Africa, came to Eurasia. On the European continent, it evolved into a distinctive variant of Homo neanderthalensis, adapted to a colder environment. Meanwhile, in Africa, the anatomically modern human (Homo sapiens) appeared. H. neanderthalensis began to die out some 50,000 years ago, unable to adapt to climate change and unable to compete with the African H. sapiens, who had better hunting, communication, and probably reasoning skills as well. Read more about the history of the human species in our article “Anthropologist Viktor Černý in search of modern human origins”, which focuses on the research of genetic traces of the anatomically modern human. |

Prepared by: Leona Matušková, External Relations Division, CAO of the CAS, drawing on the press release of the CAS

Translated by: Tereza Novická, External Relations Division, CAO of the CAS

Photo: Jana Plavec, External Relations Division, CAO of the CAS; Roman Garba; Vitaly Usyk

The text and photos labeled (CC) are released for use under the Creative Commons licence.

The text and photos labeled (CC) are released for use under the Creative Commons licence.

Read also

- New record set for neutrino mass: one million times less than an electron

- On the trail of the endangered little owl: searching for newly hatched owlets

- Teen scientist breaks barriers: No child is a lost cause

- The Czech Academy of Sciences has appointed its new leadership for 2025–2029

- Literature is tied to its historical context. How can we read between the lines?

- Radomír Pánek: The Academy must be united, strong, and proactive

- A springtime booster: The healing potential of tree buds

- A novel compound that protects bone cells may benefit diabetic patients

- New interactive exhibition at the CAS showcases materials shaped by genius ideas

- Leaf growth, root formation, and reproduction – Look to hormones for the answer

The Czech Academy of Sciences (the CAS)

The mission of the CAS

The primary mission of the CAS is to conduct research in a broad spectrum of natural, technical and social sciences as well as humanities. This research aims to advance progress of scientific knowledge at the international level, considering, however, the specific needs of the Czech society and the national culture.

President of the CAS

Prof. Eva Zažímalová has started her second term of office in May 2021. She is a respected scientist, and a Professor of Plant Anatomy and Physiology.

She is also a part of GCSA of the EU.