Threads of history: what can archaeological textiles reveal?

10. 06. 2024

Bones, ceramic shards, and jewelry give archaeologists clues about ancient history. In contrast, fragments of centuries-old textiles long seemed worthless, yet they too offer unique testimonies, as shown by the fabrics found in graves at Prague Castle. These allowed researchers to figure out what Charles IV and his wives wore and whether St Ludmila could already have had attire made of Chinese silk. You can read the story, published in Czech in A / Magazine, below.

The emperor was laid out on a bier covered with a golden quilt and cushions. Adorned with white gloves and a pleiad of rings, the body dressed in gilded royal purple trousers and cloak. In these winter days, the sun set very early, the bleak weather echoing the mood in the streets of Prague. It was December 1378, and already for several days, the city’s inhabitants and visitors had been experiencing an exceptional moment in time and place: the funeral of Charles IV, King of Bohemia and Holy Roman Emperor.

We do not know exactly what the attire of the deceased ruler on that occasion looked like. The brief description above comes from the recollections of the anonymous author of the Augsburg Chronicle. However, we can assume that the clothing intended for the ruler’s final journey was made from the finest fabrics available at the time. After all, clothes maketh the man, and even in death, the emperor’s attire was meant to symbolize his power and glory. But what materials did the imperial tailors actually have at their disposal? Which distant lands did the fabrics arrive from, and how did they reach the market in Central Europe?

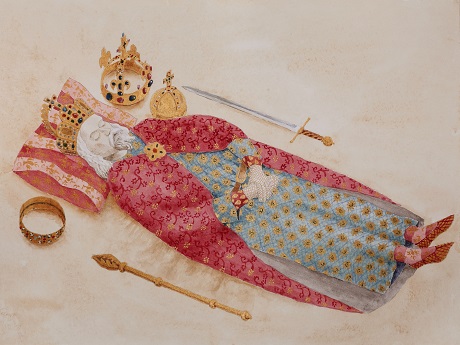

Reconstruction of the funeral attire and accessories of Charles IV. (Illustration: Petr Chotěbor, featured in the book Textiles from Archaeological Research at Prague Castle).

Rags from the crypt

Chronicles and memoirs provide little information about age-old fashion trends. That is why even small remnants of textiles preserved in graves are a valuable source. In the case of Charles IV, several pieces of fabric were found in the crypt of the royal tomb in the St. Vitus Cathedral in Prague, which archaeologists opened in 1928.

At that time, there were no available technologies that could provide relevant data about centuries-old fabrics. Consequently, experts did not consider the fabrics particularly valuable for research. “The royal crypt was in very poor condition and in need of reconstruction, so its contents had to be removed. Unfortunately, the textiles found in it received minimal scholarly attention, and records about them were, from today’s perspective, utterly inadequate,” explains textile archaeologist Milena Bravermanová, who thirty years ago was the one to initiate systematic care for archaeological textiles in our country.

|

Textiles from the tombs of Prague Castle Systematic archaeological investigations at Prague Castle began after 1859, following the establishment of the Association for the Completion of St. Vitus Cathedral at Prague Castle. The first archaeological textile found in the Castle's vicinity were pieces of fabric used as a covering for part of Bishop Ondřej's skull (13th century) – discovered by workers in the wall of the St. Wenceslas Chapel in 1888. In 1911, experts removed several fabrics from the tomb of St. Wenceslas. The largest collection of textile artifacts comes from 1928, when archaeologists opened the graves of bishops, cathedral builders, and most notably, the crypt of the royal tomb. |

In the early 1990s, while working in the Heritage Conservation Department of the Office of the President of the Czech Republic, the archaeologist was tasked with organizing and documenting items from the graves at Prague Castle, mostly textiles. “I said, well, I sew a little, so I’ll give it a try,” Bravermanová recalls with a chuckle today. She was about to take on a very challenging task.

Not only were there no precise records of the textiles from the crypt, but the individual pieces were not kept in one place, and some were even lost over time. In 1928, the experts of that time regarded the textiles from the graves more as curiosities than anything else—so much so that they sometimes kept small cuts as souvenirs or gave them to friends. “One of my tasks was to try to track down the lost pieces of textiles scattered across various private collections,” Bravermanová says.

In Czech archaeological lingo, textiles are humorously referred to as “rags,” as if they were merely dirty, useless items. “We sometimes joke about it, but the truth is that this was often the approach taken. Fortunately, this is changing, and today, textile archaeology is a firmly established part of our field.”

|

PhDr. Milena Bravermanová

Milena Bravermanová studied archaeology and history at the Faculty of Arts, Charles University in Prague. She began working at the National Museum in Prague in 1986 and joined the Heritage Conservation Department of the Office of the President of the Czech Republic in 1990. Three years later, she became the curator of archaeology and textiles in the Department of Art Collections at the Prague Castle Administration, where she organized the depositories and established a specialized restoration workshop. She worked on projects at the Institute of Archaeology the Czech Academy of Sciences in Prague from 2018 to 2023. She played a pivotal role in founding the field of textile archaeology and co-founded the corresponding academic discipline. Dr. Bravermanová lectures on prehistoric and medieval textiles and archaeological textile research methods at the Institute of Archaeology, Faculty of Arts, Charles University in Prague, and the Institute of Archaeology and Museology at Masaryk University in Brno. |

Preserving the textiles

Some textile artifacts, including those from the royal crypt, got into the hands of restorers as early as the 1980s. However, from today’s perspective, their interventions were often problematic. Common practices included excessive use of chemicals during cleaning, the removal of original stitches, and the application of modern backing materials to medieval fabrics. Moreover, the restoration process was not properly documented in writing or photographs, and the original condition of the artefacts before intervention was not described.

“The goal of textile restoration is primarily to stabilize the material, ensuring it can endure over time. The largest amounts of dirt must be removed, which can cause further degradation, but interventions on the original textile should be minimal. All interventions must be reversible,” explains Helena Březinová from the Institute of Archaeology of the CAS, Prague.

“One example of inappropriate restoration during the 1980s is the hat of Emperor Rudolf II, which somehow got shrunk,” the researcher adds. Fortunately, the field has advanced significantly since then, thanks in no small part to the pioneering work of Milena Bravermanová and subsequently Helena Březinová. Their efforts have led to archaeological textile conservation being taught at universities, fostering new generations of specialists in this rather specific discipline.

|

Royal fabrics in textile schools In 1928, when archaeologists opened and retrieved the contents of the royal crypt at Prague Castle, the valuable artefacts did not receive the attention they deserved. At that time, textile archaeology as a field did not exist yet, nor were there methods available for the restoration and study of archaeological textiles. In 1930, experts sent some fabrics from the royal tomb’s crypt to the Christian Academy in Prague to attempt to stabilize and prevent them from completely disintegrating. The outcome of this effort remains unknown, as there is no report on the results. Simultaneously, several pieces of the original fabrics (reportedly 26 different types) were distributed to various textile schools in Czechoslovakia. Students were tasked with weaving replicas based on these originals for display purposes. Two albums were created from these replica samples, one of which is now housed in the Museum of Decorative Arts in Prague. The other has been lost. The medieval fabrics were eventually returned to Prague Castle, but they arrived bundled together, again without proper documentation, with apparently some pieces missing. As recently as 2016, a fragment of archaeological fabric from Prague Castle was discovered at the Secondary School of Textile Crafts in Ústí nad Orlicí. |

The number of scholarly works on the subject is on the rise as well. Together with her colleague Jana Bureš Víchová from the University of Chemistry and Technology (Prague), Bravermanová and Březinová are the authors of a new comprehensive monograph on archaeological textiles. The study Textiles from Archaeological Research at Prague Castle comprises a total of 270 entries documenting individual textile fragments recovered from graves and tombs within the Prague Castle complex. It also offers an extensive theoretical introduction to the study of archaeological textiles, information related to Prague Castle as a burial site for historical figures, and descriptions of the medieval textile trade and contemporary fashion.

Helena Březinová and Milena Bravermanová from the Institute of Archaeology of the Czech Academy of Sciences in Prague, along with Jana Bureš Víchová from the University of Chemistry and Technology in Prague, are the authors of the book Textiles from Archaeological Research at Prague Castle.

The book’s cover features a close-up of a section of fabric from Emperor Charles IV’s burial attire, about which the researchers discovered remarkable details. “We consider it one of the highlights of the entire collection, and the book characterizes it from every possible angle,” Bravermanová points out.

Based on references in written sources, experts already assumed that rulers were buried in ceremonial robes (similar to those worn by clergy). “We have unequivocally confirmed this theory. In the specific case of Charles IV, for instance, we identified a dalmatic, which is a liturgical vestment worn during church services,” the archaeologist adds.

Another important – and surprising – finding was determining the origin of the fabric. It came from as far away as Central Asia, possibly even China.

What did Charles IV wear?

The phenomenon of Central Asian fabrics on the European medieval market remained largely unexplored for a long time. More comprehensive scientific information on the subject didn’t begin to emerge until about twenty years ago, coinciding with the advancement of research methods. American, German, and Swiss textile historians were the first to delve into the topic.

“We learned about it from foreign literature and examined our collections with fresh eyes. Suddenly, we realized that we too had textiles of Central Asian origin, and in considerable quantities. We even documented unique patterns of design that have not survived anywhere else,” Bravermanová says.

Apart from one velvet fabric of Italian origin, the burial robe of Charles IV was made entirely of fabrics from Central Asia. Remarkably, these fabrics dated from the first half of the 14th century, with the emperor dying in 1378. These were extremely rare and luxurious textiles for their time, indicating that the Luxembourg court was wealthy enough to purchase them in advance and later use them for the emperor’s burial robe.

Maternity dresses

Central Asian fabrics were also found in the graves of women associated with Charles IV (his wives and daughter-in-law). However, in their case, determining the exact origins is very complicated. That is because in 1590, their remains were transferred to a new royal tomb, and in 1612, when it was necessary to make room for the sarcophagus of the deceased Emperor Rudolf II, they were put together with the bones of John of Görlitz and Wenceslaus IV (sons of Charles IV).

This fabric with motifs of fortifications and animals from the late second half of the 14th century originated from Italy. It was used to make a garment for the funerary attire of one of Charles IV's wives.

“Due to the transfer and merging of remains, the situation is unfortunately not clear-cut, but there are certain clues that have allowed us to identify fragments of some textiles,” Březinová says. Unfinished armholes or unattached sleeves, for instance, can suggest hastily prepared garments for a woman who died unexpectedly or whose body was difficult to handle.

This might apply to an examined fabric with a bird motif, adorned with the then fashionable pseudo-Kufic (pseudo-Arabic) script, likely of Italian origin from the second half of the 14th century. It was used to make a bodice (an item of clothing covering the upper body). It belonged either to Charles IV’s last wife, Elizabeth of Pomerania, or to the wife of Charles’ son Wenceslaus IV, Johanna of Bavaria.

Fabrics likely used for maternity dresses can be linked to Anna of Schweidnitz, Charles’ wife, who died in childbirth. These fabrics are bedecked with animals and palmettes (ornaments resembling radiating palm leaves) likely from the Middle East or Italy. Part of a bodice has survived, which flared out down towards the waist, suggesting an enlarged pregnancy belly, as well as a wide skirt gathered at the waist.

From the preserved remnants of other dresses, it is evident that the tailors of the time made them using luxurious fabrics with distinctive original designs. “They feature things like human figures, ships, city walls, peacocks, gazelles, eagles, but also lotus flowers and Chinese birds,” Březinová notes.

|

PhDr. Helena Březinová, Ph.D.

Helena Březinová studied archaeology and history at the Faculty of Arts, Charles University in Prague. She focused on archaeological textiles in her thesis (“Slavic Textile Production in the 6th–12th Centuries”) and in her dissertation (“Textile Manufacture in the Czech Lands in the 13th–15th Centuries”). Since 1994, she has worked at the Institute of Archaeology the Czech Academy of Sciences in Prague, initially in the research department of Prague Castle and, since 2007, at the Restoration Laboratory, which she currently heads. She is one of the founders of the study program textile archaeology taught at Czech universities. Dr. Březinová lectures on textile production in prehistoric and early to high medieval periods at the Institute of Archaeology, Faculty of Arts, Charles University in Prague, and the Institute of Archaeology and Museology at Masaryk University in Brno. |

Christening outfit

A rare find comprises the preserved fragments of a baby’s christening outfit. It is unknown who it belonged to, and the circumstances of its discovery are intriguing. The fragments were found in the tomb of Prince Břetislav II, who died in 1100. Gravesites would often shift as the Prague Castle complex underwent construction changes. Břetislav’s body originally rested in the Romanesque Basilica of St. Vitus, which later gave way to the construction of the cathedral we know today.

The transfer of Prince Břetislav’s remains was supposed to occur in 1373, and the new grave was marked with a lead plate bearing the ruler’s name. However, as shown by an anthropological survey in 2002, Břetislav was not in the tomb. Instead, archaeologists found the remains of at least five individuals: two women, one person of indeterminate sex, a newborn, and a toddler. Among the children’s bones were tiny textile fragments, about which modern methods have revealed incredible details.

The outfit consisted of a shirt and pants, both with a relatively complicated cut that bore the characteristics of both undergarments and basic clothing for adults in the High Middle Ages, namely a shirt, tunic, and breeches. Given the quality of the fabrics and the precision of the craftsmanship, it is assumed that the outfit was imported, possibly from Spain, where similar fine fabrics with a crêpe effect were woven.

Textile archaeologists believe the garment in question was in fact christening clothing because it included a hood adorned with a cross embroidered with metallic thread. No other children’s christening outfits from the medieval period have survived, making this a truly unique find.

The name and origin of the baby remain uncertain; it might have been the son of Přemysl Otakar II or Wenceslaus II, as it is known both children died shortly after birth.

“Not everything can be proven. There are many unknowns surrounding the origins of these garments, as we have mentioned in our book,” Bravermanová says. “The interpretation of conclusions can change with the development of our field. In the book, we offered readers very detailed information and a foundation for further research,” Bravermanová concludes.

The restoration of fabric featuring motifs of tree trunks, rosettes, pomegranates, and flowers is detailed in the book Textiles from Archaeological Research at Prague Castle.

Chinese silk in the Czech lands

An example of how new context can completely alter the interpretation of the past is the phenomenon of luxury fabrics of Central Asian origin. Until the end of the 20th century, it was believed that most preserved fragments of clothing in our region were from Europe – Italy, specifically.

Goods, including fabrics from China and Central Asia, began moving westward around the 2nd century BCE via the Silk Road. However, these fabrics primarily reached the Byzantine Empire and the territories of the modern Middle East. Direct access further into Europe was limited for a long time. Thus, emerging European elites had access to luxury textiles from the Far East only indirectly, often by means of gifts from Byzantine emperors. This is how the princes of the Great Moravian Empire and later the Přemyslid dynasty came into contact with Asian silk.

|

Silk dresses of St. Ludmila? Rulers of the Great Moravian Empire and early medieval Bohemia already had access to luxury silk. It is highly likely, then, that so did St. Ludmila. However, we lack direct evidence, since none of her burial garments have survived. She was buried in 921 in Tetín, and her remains were transferred to Prague Castle in 925. As was customary for saints, the remains were venerated, with parts being taken out, wrapped in cloth, and transported. The textiles preserved from St. Ludmila's grave thus date from a period later than her death. Nevertheless, they are among the most valuable archaeological textiles we have, primarily due to their connection to the Czech national saint. These include a patterned fabric of Byzantine origin from the turn of the 10th and 11th centuries and an unpatterned fabric produced in an early medieval silk workshop in Asia. |

Later, Europeans themselves learned the technology of producing luxury silk. By the mid-13th century, silk textiles were being woven in northern Italian cities such as Venice, Bologna, and Florence. During the reign of Charles IV, trade between these cities and the Czech kingdom flourished, making it easy for the wealthy elite to acquire luxury fabrics. This led to the assumption that the royal court primarily used materials of Italian origin.

Today, however, we know that they used much more than just Italian materials. Fragments of the burial robes of Charles IV and his relatives clearly show that by the late 14th century, the ruling family also utilized rare fabrics from distant Central Asia and China. Thanks to modern methods used in archaeological textile research, we are now uncovering previously unknown details about the final journey of the Father of the Nation.

*

The article was published in Czech in the 4/2023 issue of the A / Magazine of the CAS:

4/2023 (version for browsing)

4/2023 (version for download)

Written and prepared by: Leona Matušková, External Relations Division, CAO of the CAS

Translated by: Tereza Novická, External Relations Division, CAO of the CAS

Photo: Shutterstock; Jana Plavec; restoration images from Textiles from Archaeological Research at Prague Castle

Read also

- Czech scientists contribute to developing eco-friendly, affordable solar cells

- An epileptic seizure doesn’t always strike out of the blue, says Jaroslav Hlinka

- Radomír Pánek nominated for the next President of the CAS

- Four CAS projects get ERC Consolidator Grants, each to receive two million euros

- Groundbreaking study maps brain’s recovery process after stroke

- A / Magazine: light, the dawn of quantum computing, and no man’s lands

- Of Mice and Men: Researchers reveal link between human and mouse migration paths

- Czech and Saxon Academies of Sciences to strengthen cooperation on key issues

- Laser micromachining: inspired by sharks

- CAS researchers received the 2024 Praemium Academiae and Lumina Quaeruntur

The Czech Academy of Sciences (the CAS)

The mission of the CAS

The primary mission of the CAS is to conduct research in a broad spectrum of natural, technical and social sciences as well as humanities. This research aims to advance progress of scientific knowledge at the international level, considering, however, the specific needs of the Czech society and the national culture.

President of the CAS

Prof. Eva Zažímalová has started her second term of office in May 2021. She is a respected scientist, and a Professor of Plant Anatomy and Physiology.

She is also a part of GCSA of the EU.